Welcome to the Polycrisis

A new view on the challenges facing the UK over the next decade and how green politics should respond

July 2024 - a sigh of relief

After the Brexit- and COVID-induced turmoil of the last 8 years, the 2024 UK general election was widely expected by the mainstream media to herald a new era of relative calm and progress in UK politics and society — “a return to normality”, neatly summed up by Otto English in this tweet.

This expectation had been reinforced by Labour’s projection of a centrist, professional technocratic culture and its anodyne General Election manifesto, with its commitment to fiscal rules, its focus on growing the economy, and its acceptance of the current distribution of power and wealth in the UK.

Reality bites

This expectation of calm and growth was unfounded even in its own terms, based as it was on a failure to acknowledge that the Tories have left the UK in a mess, and hence that significant investment will be needed just to keep public services functioning.

Unsurprisingly, almost immediately following the General Election,, Labour reneged on its manifesto, claiming it had found an unexpected “black hole” in government budgets, and using that as an excuse to raise taxes and reduce benefits, primarily hitting the already vulnerable such as pensioners, small businesses, councils and charities. Even the spending increases it enabled will at best halt the overall further decline, not radically improved public services.

In response, Labour is now pinning its future on the belief that economic growth will return, which will in turn provide the tax revenues from which it can eke out some further investment, and it has been prepared to sacrifice its supposed social and environmental principles in this pursuit. But already this growth is proving illusory - and this was before the volatility that Trump’s actions look like causing have a chance to feed into the global economy.

Why this disconnect?

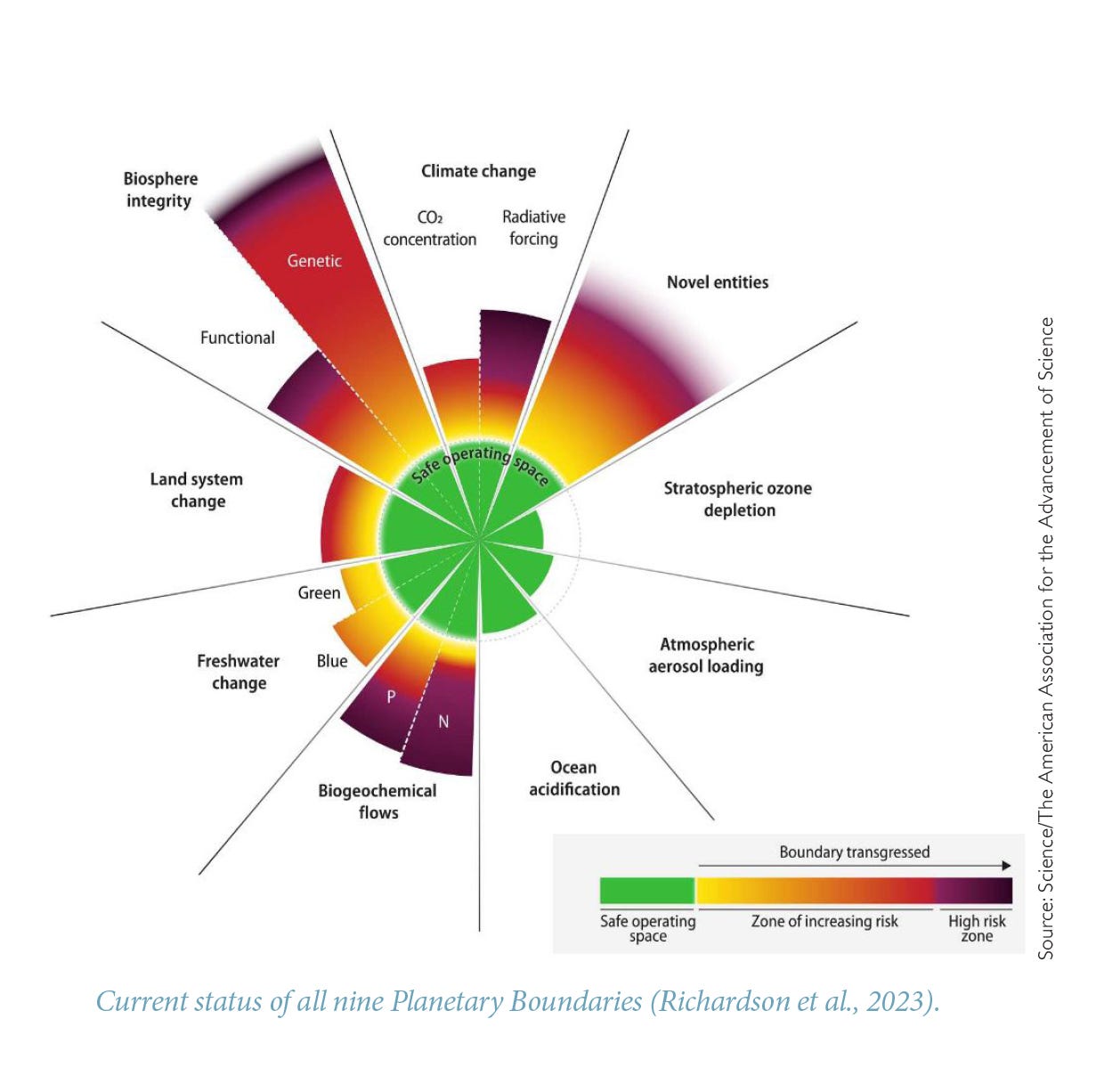

Mainstream analysis still assumes that infinite growth is possible, that there are no fundamental limits imposed by planetary systems. It is this fundamental disconnect between the reality that the world is starting to reach planetary limits versus a mainstream assumption that infinite growth is possible. Planetary limits will result in a snowballing cascade of environmental, economic and political challenges (nationally and globally - the polycrisis).

As it is bought into the mainstream analysis, the Labour government and the wider establishment is not ideologically capable of anticipating the various ways in which the polycrisis manifests. So it will not take the rapid, radical, systemic action needed, and instead will often unintentionally exacerbate these very issues (e.g. by expanding air travel, investing in unproven Carbon Capture and Storage technology etc.)

Limits to Growth — the source of the polycrisis

To understand why mainstream thinking is unable to see or address the challenges of planetary limits, it is first worth stepping back to look at the first systems dynamics analysis of the interaction between the global ecosystem and global civilisation. The model, and the resulting report “The Limits to Growth” released in 1972, showed that if humanity did not adjust the global economy so that it operated within planetary limits, then the most likely scenario was that the global economy would eventually exhaust easily available resources, that the impact of pollution would increase, and that food, wealth and population would eventually peak and inexorably fall.

As expected by the model, total wealth has increased over the last fifty years, and this can be seen in the emergence of a global middle class and by the increased in wealth of even the richest countries (and people). But also as expected by the model, this has been achieved by unsustainable use of resources, and by ever-increasing pollution resulting from resource consumption.

Mainstream thinking for the last half-century has not effectively rejected the conclusions of that report and its subsequent updates. An unscientific assumption that economic growth was and continues to be possible and necessary is the foundation of our economic system, and hence our society, media and politics. So while there have been recent efforts to shift at least some elements of the global economy towards a more sustainable model (for example the implementation of some renewable energy generation), these have been too little, too late. Subsequent re-runs of the The Limits to Growth model using updated data show that the peaking and then decline in global food, wealth and population has only been delayed, not avoided.

The response of the elite to the threat of collapse

Analysis of the factors that have caused previous civilisations to collapse has shown that the behaviour of the elites is critical to whether action is taken early and effectively. Elite overproduction describes the condition of a society that is producing too many potential elite members relative to its ability to absorb them. The vast increase in inequality and the concentration of wealth in the top 1% over the last 30 years in many countries is evidence that this is happening globally.

Limits to Growth are exacerbating that tension, as they start to reduce the ability of societies to support those elites, and as with previous civilisations collapses the likelihood is that our elites (and e;lite aspirants) will focus on competing to retain’gain their share of a decreasing amount of wealth. If this happens then it will drive further inequality and poverty for the majority, and will take attention away from addressing the real issues quickly and rapidly enough to avoid collapse - I see Trump and Musk are an example of this.

Limits to Growth as they are starting to affect the UK

The UK led the industrial revolution, and it reached the limits of its own resources during the 19th and early 20th centuries, so that in the 21st century the UK now has to import 40% of its food and 37% of its energy. The UK is also hugely dependent on raw materials and manufactured goods from overseas, and is similarly dependent on shipping out waste materials for (it hopes/pretends) reuse or recycling.

As the world now begins to really run up against planetary limits, the UK’s high dependence on resources sourced from overseas has meant that it has been on the sharp end of those first shocks— notably it was one of the main causes of the recent (and ongoing) cost of living crisis.

As and when the mainstream should have had to face the facts (e.g. in the 2007 Great Financial Crash, or the cost of living crisis), the response of the elites has been to “extend and pretend”, even though in reality in the UK living standards have fallen for all but the super-rich.

Where the UK is now

The Tories had a rightly terrible general election, in part because they had no answers to the challenges of the 21st century but also because they were unwilling to fully adopt the only other easy right-wing solution — populist, nationalist culture wars and scapegoating of vulnerable groups. So unless, and until, they develop some compelling answers, or give in to the lure of populism, they will not be a real force in UK politics.

Under the UK’s FPTP system, Labour was the natural beneficiary of the Tory collapse, gaining a strong majority. But this was achieved on a relatively small vote share, which under normal circumstances would have caused them to lose a general election. Labour has already also shown it is also lacking answers to the challenges of the 21st century, and as its vote share drops, it has started to embrace populist, nationalist culture war issues and scapegoating of vulnerable groups (notably migrants and benefits recipients).

The LibDems did relatively well through careful targeting of effort and by being a “safe” alternative for disaffected Tory voters in specific seats and demographics. But again, they have no real understanding of the challenges facing the UK, and are choosing to campaign only on the limited number of issues they feel comfortable with.

Positioned on either end of the political spectrum from Labour are the Green Party and Reform, both of whom had a relatively successful general election campaign in terms of vote share, but of course with their MP totals constrained by the FPTP system. Reform is of course a populist, grievance-based politics that assigns blame to marginalised, foreign and vulnerable groups. The Green Party is the only organised political movement in the UK that understands that it is the combination of elite capture of wealth and power coupled to an unsustainable economy that has driven, and will continue to drive inequality, poverty and environmental collapse both in the UK and globally.

The next 4 years

Labour’s relatively small vote share leaves it open to a catastrophic collapse in its number of MPs from either or both of the emergence of a dominant party on the right and disaffection to the left.

On that basis, all four other parties will be looking to critique Labour’s inevitable failures, take ever-increasing numbers of local councillors, and ultimately be positioned to take many more MPs at the next general election. Given the type of challenges that will arise over the next 5 years, and the inability of the traditional, mainstream responses to explain and address them, only Reform and the Greens seem truly placed to respond convincingly - with Reform making the early running through their access to significant donor funding plus a benign media environment.

My areas of focus

This newsletter takes as its scope how those limits to growth begin to manifest, and the political and societal responses to those limits. There will be a particular focus on green politics, notably what the UK Green Parties should do so that they successfully offer a response to those challenges, and that we get as close as we can to delivering a socially just and environmentally sustainable world. I’m looking forward to it!